Assessing U.S.-Flag Fleet Capacity for Venezuelan Crude Oil Transport

Policy Brief | January 15, 2026

Executive Summary

On January 8, 2026, major maritime labor unions submitted a letter to the current administration proposing that all crude oil imports from Venezuela be transported exclusively on U.S.-flag vessels. An analysis was conducted on the operational feasibility of such a mandate.

Key Findings:

The U.S.-flag international tanker fleet contains zero crude oil carriers. All 17 vessels currently in service are product tankers designed for refined petroleum transport.

The Jones Act domestic fleet includes 13 crude tankers, but these are fully committed to essential domestic routes and cannot be redirected without triggering supply disruptions.

Expanding the fleet faces structural constraints: government subsidy programs that sustain U.S.-flag operations are at or near capacity, and domestic shipyards are booked through the end of the decade.

The United States lacks sufficient mariners to crew additional vessels. The commercial mariner workforce has declined to approximately 10,000, a shortage acute enough that the Navy mothballed 17 supply ships in 2024 for lack of qualified crews.

Implemented as written, the proposed mandate would function as a prohibition on Venezuelan crude imports rather than a mechanism for expanding American maritime employment.

Background

On January 8, 2026, the presidents of four maritime labor organizations transmitted a joint letter to Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Secretary of War Pete Hegseth. The correspondence expressed support for "proposals that would mandate all crude oil imports from Venezuela to be transported exclusively on U.S.-flag vessels crewed by American mariners."

The letter frames this proposal as consistent with Executive Order 14081, "Restoring America's Maritime Dominance," signed April 9, 2025, which directs the development of a comprehensive Maritime Action Plan to revitalize U.S. commercial shipbuilding and expand the U.S.-flag fleet.

This analysis examines a narrow question: Does the current U.S.-flag fleet possess the capacity to execute such a mandate?

Crude Carriers and Product Tankers

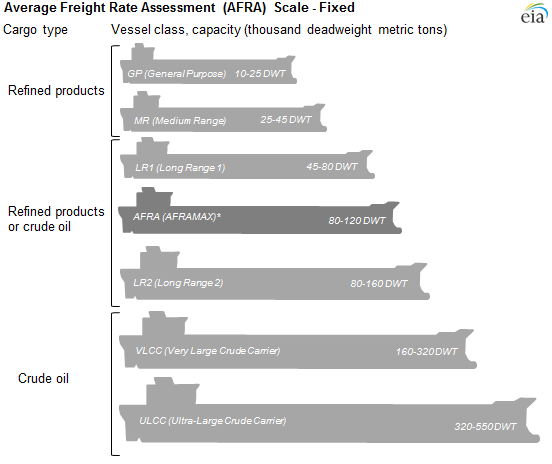

Tankers are ships designed to transport energy products in bulk, such as crude oil, gasoline, jet fuel, and LNG. The maritime industry distinguishes between different types of tankers, including crude tankers and product carriers.

Crude tankers transport unrefined petroleum from production sites to refineries. These vessels feature large, uncoated cargo tanks optimized for single-cargo operations. Crude tankers are typically larger vessels—Aframax class (80,000–120,000 DWT), Suezmax (120,000–200,000 DWT), or Very Large Crude Carriers (200,000+ DWT)—reflecting the economics of bulk transport from concentrated export terminals to refinery facilities.

Product tankers transport refined petroleum products (gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, heating oil) from refineries to distribution terminals. These vessels feature multiple segregated cargo tanks, each equipped with independent pipeline and pump systems to prevent cross-contamination between different product grades. Product tankers are typically smaller, reflecting the more dispersed distribution patterns of refined products.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=17991

These vessel categories are generally not operationally interchangeable. Product tankers lack the systems and capabilities required for crude oil transport, particularly the sour, lower-quality grades characteristic of Venezuelan production.

U.S.-Flag Fleet Composition

The U.S.-flag oceangoing fleet operates under two distinct regulatory frameworks, each with different implications for Venezuelan crude transport.

Jones Act Domestic Tankers

The Jones Act (Merchant Marine Act of 1920) requires vessels transporting cargo between U.S. ports to be U.S.-built, U.S.-flagged, U.S.-owned, and U.S.-crewed. As of mid-2025, 54 oceangoing tankers meet these requirements.

These vessels are not available for Venezuelan crude imports. Analysis of Jones Act fleet operations conducted in November 2025 determined that these tankers serve routes where pipeline infrastructure is absent or insufficient for demand:

Alaskan Crude Transport (14 vessels, 44% of tanker capacity): Transporting crude oil from Alaska to Washington and California refineries, a route with no pipeline alternative

Florida Petroleum Service (20 vessels, 28% of capacity): Delivering refined products from Gulf Coast refineries to Florida, which has no in-state refineries and limited pipeline access

East Coast Service (7 vessels): Supplementing limited pipeline capacity to Eastern Seaboard markets

Other domestic routes (13 vessels): West Coast distribution, renewable diesel transport, inter-Gulf movements, and Puerto Rico LNG service

The Jones Act fleet includes 13 crude tankers, with the majority dedicated to transporting Alaskan crude to refineries in Washington State and California—a route with no pipeline alternative.

| IMO | Vessel Name | Year | Barrel Capacity | Route Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9206114 | POLAR DISCOVERY | 2003 | 994,034 | Alaskan Crude Transport |

| 9244659 | ALASKAN FRONTIER | 2004 | 1,300,355 | Alaskan Crude Transport |

| 9271432 | ALASKAN LEGEND | 2006 | 1,326,898 | Alaskan Crude Transport |

| 9244673 | ALASKAN NAVIGATOR | 2005 | 1,326,898 | Alaskan Crude Transport |

| 9642095 | CALIFORNIA | 2015 | 777,421 | Alaskan Crude Transport |

| 9244063 | POLAR ADVENTURE | 2004 | 994,034 | Alaskan Crude Transport |

| 9193551 | POLAR ENDEAVOUR | 2001 | 994,034 | Alaskan Crude Transport |

| 9250660 | POLAR ENTERPRISE | 2006 | 994,034 | Alaskan Crude Transport |

| 9193563 | POLAR RESOLUTION | 2002 | 994,034 | Alaskan Crude Transport |

| 9642083 | WASHINGTON | 2014 | 817,661 | Alaskan Crude Transport |

| 9118628 | OREGON | 1997 | 349,022 | Inter-Gulf Coast Transport |

| 9244661 | ALASKAN EXPLORER | 2005 | 1,300,355 | Gulf Coast to East Coast |

| 9118630 | SEABULK PRIDE | 1998 | 340,832 | Gulf Coast to Florida |

Source: MARAD June 2025 fleet report; Balsa Research internal analysis

Redirecting these vessels to international service would create immediate domestic supply disruptions, with consequences including:

Curtailment of Alaska's oil production and associated economic activity, which provides 24% of the state’s wage and salary jobs, and $4.8 billion in annual wages

Collapsing the economies of multiple West Coast refinery towns, including direct and indirect job losses, and decreases in direct economic output

Creating a domestic fuel shortage

No reserve or replacement vessels exist within the domestic fleet. For purposes of this analysis, Jones Act crude tankers are considered fully committed and unavailable for Venezuelan service.

U.S.-Flag International Fleet Tankers

For international voyages, including Venezuela-to-U.S. crude transport, the relevant asset base is the U.S.-flag international fleet. These vessels are U.S.-owned and U.S.-crewed but foreign-built, rendering them ineligible for domestic Jones Act service while permitting international operations.

According to the Maritime Administration's June 2025 fleet report, 18 tankers were registered in the U.S.-flag international fleet. One vessel (YOSEMITE TRADER) reflagged to foreign registry in November 2025, reducing the current fleet to 17 tankers.

All 17 remaining vessels are product carriers. The U.S.-flag international fleet contains zero crude oil tankers.

| IMO | Vessel Name | DWT | Tanker Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9430284 | ALLIED PACIFIC | 46,151 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9700483 | BADLANDS TRADER | 50,034 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9561148 | HAINA PATRIOT | 6,765 | Oil Products Tanker |

| 9435894 | OVERSEAS MYKONOS | 51,711 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9435909 | OVERSEAS SANTORINI | 51,662 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9862944 | OVERSEAS SUN COAST | 50,332 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9809564 | POHANG PIONEER | 6,510 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9809576 | REDWOOD TRADER | 6,510 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9708760 | SHENANDOAH TRADER | 50,124 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9448334 | SLNC GOODWILL | 50,326 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9383663 | SLNC PAX | 6,957 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9693020 | STENA IMPECCABLE | 49,737 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9666077 | STENA IMPERATIVE | 49,777 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9390032 | STENA POLARIS | 64,917 | Oil Products Tanker |

| 9712292 | TORM THOR | 49,667 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9712307 | TORM THUNDER | 49,667 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

| 9726487 | TORM TIMOTHY | 49,667 | Chemical/Oil Products Tanker |

Source: MARAD June 2025 fleet report; vessel classifications verified via VesselFinder registry data.

The proposed mandate cannot be executed with existing U.S.-flag assets. The number of crude-capable vessels available for Venezuelan imports is zero.

Constraints on Fleet Expansion

Three structural factors limit the feasibility of expanding U.S.-flag crude tanker capacity within policy-relevant timeframes.

Government Support Program Capacity

Operating under the U.S. flag imposes significant cost premiums relative to foreign-flag alternatives, primarily due to American crewing requirements and regulatory compliance obligations. U.S.-flag vessels in international trade depend substantially on government support programs that offset these differentials.

Of the 17 tankers in the current U.S.-flag international fleet, 15 participate in either the Maritime Security Program (MSP) or Tanker Security Program (TSP). The MSP provides stipends of $5.8 million per vessel annually; the TSP provides $6 million annually. These programs exist to maintain commercially operated vessels available for Department of Defense sealift requirements during contingencies.

| IMO | Vessel Name | DWT | TSP | MSP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9430284 | ALLIED PACIFIC | 46,151 | N | Y |

| 9700483 | BADLANDS TRADER | 50,034 | N | Y |

| 9561148 | HAINA PATRIOT | 6,765 | N | Y |

| 9435894 | OVERSEAS MYKONOS | 51,711 | N | Y |

| 9435909 | OVERSEAS SANTORINI | 51,662 | Y | N |

| 9862944 | OVERSEAS SUN COAST | 50,332 | Y | N |

| 9809564 | POHANG PIONEER | 6,510 | N | Y |

| 9809576 | REDWOOD TRADER | 6,510 | N | N |

| 9708760 | SHENANDOAH TRADER | 50,124 | Y | N |

| 9448334 | SLNC GOODWILL | 50,326 | N | N |

| 9383663 | SLNC PAX | 6,957 | N | Y |

| 9693020 | STENA IMPECCABLE | 49,737 | Y | N |

| 9666077 | STENA IMPERATIVE | 49,777 | Y | N |

| 9390032 | STENA POLARIS | 64,917 | N | Y |

| 9712292 | TORM THOR | 49,667 | Y | N |

| 9712307 | TORM THUNDER | 49,667 | Y | N |

| 9726487 | TORM TIMOTHY | 49,667 | Y | N |

Program enrollments retrieved from MARAD’s June 2025 fleet report. Enrollments highlighted in red.

However, both programs operate under congressionally authorized capacity limits:

Maritime Security Program: All 60 operating agreements are currently filled

Tanker Security Program: 9 of 10 agreements are filled; the program exclusively supports product tankers for military logistics requirements

The absence of available subsidy slots, combined with the TSP's product tanker focus, means that reflagging foreign-built crude tankers to U.S. registry lacks the economic support structure that sustains current U.S.-flag international operations.

Domestic Shipbuildng Constraints

U.S. commercial shipyard capacity has remained structurally limited since the 1980s, with domestic yards producing approximately five large commercial vessels annually for over four decades. In the past two decades, only two crude tankers have been constructed domestically—both at Philly Shipyard under a 2011 contract, with deliveries in 2014–2015.

Philly Shipyard's current orderbook is committed through the end of the decade, including training ships, containerships, LNG carriers, and ten MR product tankers with first delivery expected in 2029. A crude tanker contract initiated today would likely yield delivery in the mid 2030s at earliest, well beyond relevant policy planning horizons.

Mariner Workforce Limitations

The United States currently employs approximately 10,000 qualified commercial mariners, a decline from over 80,000 at mid-century. This contraction has produced acute operational constraints: the Navy mothballed 17 supply ships in 2024 due to insufficient qualified crews.

Former Maritime Administrator Mark Buzby, himself a Merchant Marine Academy graduate, characterized the constraint in November 2024: "Assuming we can build ships or bring them back under U.S. flag, can we man them sufficiently? I don't think so, not without some significant changes [to training pipelines and retention].”

The unions signing the January 8 letter represent this very workforce. The American Maritime Officers, Seafarers International Union, International Organization of Masters, Mates & Pilots, and Marine Engineers' Beneficial Association collectively represent the majority of the approximately 10,000 American commercial mariners.

A cargo mandate requires mariners to execute it. The January 8 letter focuses on cargo access but does not address workforce development, training pipeline expansion, or retention initiatives, which are elements that would need to accompany any sustained increase in U.S.-flag shipping activity.

Conclusion

The maritime unions' letter articulates goals that many policymakers share: expanding the U.S.-flag fleet, creating American maritime jobs, and reducing dependence on foreign shipping. The difficulty is that the proposed mechanism presupposes fleet capabilities that do not currently exist.

The gap between Ship American rhetoric and Ship American reality is measured in missing ships and missing mariners. Closing it will require sustained investment in ship procurement capacity and workforce training pipelines. These are areas where labor, industry, and policymakers might find common ground, but the January 8 letter does not engage them.

🔆

For questions or comments, please contact info@balsaresearch.com.